Introduction:

As globalizations spreads its wings to its fullest, the distinctions between nations are becoming increasingly indistinct as international entities extend their reach to even the most remote corners of the world. While globalization fosters economic integration and cultural exchange, it also poses significant challenges to rural and cultural products, thereby impacting the livelihoods of local communities. These unique products, often steeped in heritage and tradition, are at risk of disappearing due to inadequate knowledge and financial resources.

Geographical Indication- An emerging Intellectual property right in India.

Thus, the concept of geographical indications has already started to represent a unique intersection of intellectual property rights and cultural heritage. As per WIPO Magazine 2017, IPRs will undergo a fresh revolution as GI emerged as the “sleeping beauty of IPR[1]. As per TRIPS Agreement, GI is defined as “indications which identify a good as originating in the territory of a member, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographical origin.”[2] Thus, only products with a distinctive reputation or characteristics, originating from specific locales or crafted by particular communities, qualify for the prestigious Geographical Indication (GI) tag. Some renowned examples of GIs on the global stage include California Cheese, Scotch Whisky, Basmati rice, Tuscany olive oil, Florida Oranges, Darjeeling Tea, Swiss watches and Indian Carpets., etc. every nation has formulated their own GI definitions, rules and regulations whereas India has specifically dealt this IPR Law under Geographical Indication of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act 1999 which came into effect from September 2003, in order to comply with TRIPS Agreement. Section 2 (e) of the G.I. Act, 1999 defines “Geographical Indication, in relation to goods, means an indication which identifies such goods as agricultural goods, natural goods or manufactured goods as originating, or manufactured in the territory of a country, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristics of such goods is essentially attributable to its geographical origin and in a case where such goods are manufactured goods one of the activities of either the production or of processing or preparation of the goods concerned takes place in such territory, region or locality, as the case may be.[3]” Where the duration of Registered GI tag was fixed as 10 years which could be renewed again and again through a renewal fee. This Act was specifically introduced to:

1) Define terms such as GI, producers, and distinctions of various goods identified as GI, categorized into four classes:

- i) Agricultural products

- ii) Foodstuffs

iii) Handicrafts

- iv) Manufactured goods

2) Provide a structured procedure for registration and rectification within Indian territory.

3) Introduce special provisions for trademarks.

4) Offer extensive legal regulations for penalties and remedies.

According to government statistics, 167 products were conferred with GI tags between April 2023 and March 2024, elevating India’s total to 643. Recently, there has been a pronounced emphasis on handicrafts from the northeastern states, including Tripura’s Pachra-Rignai, Meghalaya’s Garo textile, Arunachal Pradesh’s Tai Khamti textile, and Assam’s Bihu dhol. Despite the substantial progress, challenges remain in ensuring these traditional and culturally significant products receive the protection and recognition they deserve.

Challenges and issues faced by communities:

- Issue of Disparity among different states

An analysis of the current list of registered GIs reveals significant disparities among Indian states and union territories. Some states boast numerous registered GIs, while others lag with only one or two. For instance, Uttar Pradesh, Kerela, Karnataka, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra have a substantial number of GIs registered. In contrast, states like Arunachal Pradesh, Delhi, Jharkhand, and Tripura have minimal representation before the start of this year.

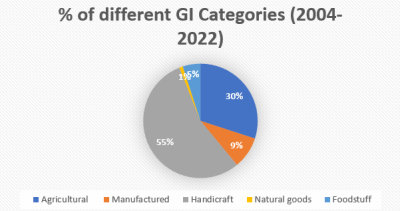

- Disparity in GI Categories

Another issue is the uneven distribution of GIs across different categories. The majority registered number of GIs amounts to agricultural goods and handicrafts, with fewer registrations in foodstuffs, manufactured goods, and natural products. While some of the most threatened ayurvedic plants and herbs came into this 1% category of natural products. Thus, there is a gap of knowledge and empowerment to some producers and artisans who failed to recognize the potential and significance of obtaining GI tags for their unique natural products. This gap hinders their ability to protect and market these valuable resources effectively.

Source: Geographical Indications Registry Office

- Issue of Technical – know how

A significant barrier in the GI registration process is the issue of technical know-how, which refers to the specialized knowledge and expertise required to navigate the intricate steps involved. This includes: –

- Understanding Legal Requirements and criteria for GI registration can be difficult for applicants who lack formal education or legal training.

- Navigating complex administrative procedures of filling application, preparing accurate documentation advertisement, hearings, and appeals, etc, which might be unfamiliar with producer or artisans.

- Lack of recourses to hire a legal representative or to even gain some legal advice, due to economic conditions.

- Post-registration monitoring and enforcement to protect the GI status against infringements.

The lack of technical know-how can lead to incomplete applications, prolonged processing times, and rejections. As till date total of 512 applications for registering GI tags are pending in Geographical indication registry office[4].

- Social and Economic Challenges

Even though Geographical Indication of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act was enacted on 1999, the hurdle remains the unawareness of the local communities towards the crucial role of GI tags. Till today many local communities and rural lack knowledge about filing for GI protection and are unaware of the remedies available to infringement of their GI. This knowledge gap perpetuates vulnerability among these individuals. While the weak and unrecognized economical condition adds more to their fragile condition in the society. Several states have incurred significant expenses in legal efforts to protect their GIs from infringement. For instance, the Tea Board of India have substantiated an economical burden of 9.4 million in order to safeguard Darjeeling from unauthorized use during its earlier phase of legal battle only.

[Image Sources: Shutterstock]

Conclusion:

In conclusion, while the Geographical Indications (GI) system in India has made significant strides in protecting traditional products, numerous challenges persist. Disparities among states, technical hurdles, and a lack of awareness pose significant obstacles to the effective registration and protection of GI products. Additionally, the uneven distribution of GI categories further exacerbates the issue, particularly hindering producers of natural products.

- Raising awareness by organizing workshops and training programs to raise GI awareness and upgrade the skills of rural weavers and manufacturers which would address social issues.

- Streamlined Registration Procedures: Simplifying and expediting the GI registration procedures can help reduce processing times and facilitate broader participation, particularly for marginalized communities.

- Offer export subsidies to economically disadvantaged producers and artisans to alleviate marketing and monitoring costs, facilitating their competitiveness in the international market. Non-profit organizations could aid in post-registration branding with government financial support.

- Strengthen GI mechanisms domestically and internationally to tackle technical challenges in monitoring infringement instances. This entails amending the Geographical Indications Act to include stricter punitive measures for violators.

- Establish branches in remote areas to enhance geographical accessibility to GI resources and services which would cater geographical challenges and issues faced by communities.

Author: Vrand Rana, in case of any queries please contact/write back to us via email to chhavi@khuranaandkhurana.com or at Khurana & Khurana, Advocates and IP Attorney.

[1] Marcus Höpperger, “Geographical Indications: From Darjeeling to Doha” WIPO Magazine 2017 available at https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2007/04/article_0003.html.

[2] Dr. Dwijen Rangnekar, Geographical Indications A Review of Proposals at the TRIPS Council: Extending Article 23 to Products other than Wines and Spirits, (ICTSD), Issue Paper No. 4 1,4, (2003)

[3] Geographical Indication of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act 1999

[4] Data taken from geographical indication registry office.