Introduction

The Indian criminal laws dated back to the times of colonialism and after around two centuries, a need was felt to revamp it. Therefore, in March 2020, the Central Government constituted a Criminal Law Reforms Committee (CLRC) that examined the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860 Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) and the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 to suggest reforms. The committee submitted its report in February 2022, with consultation from the public as well. On the basis of the report, the government introduced three new bills named the Bhartiya NyaySanhita (BNS), the Bhartiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), and the Bhartiya SakshyaSanhita (BSS) as the replacements of IPC, CrPC, and IEA respectively in Lok Sabha on 11 August 2023 that would replace the three above-mentioned laws. The bills introduced the concept of ‘Community Service’ that is considerably new for the Indian legal system as it has previously been found only in the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015.

Here, it is of essence to define ‘Community Service’ and its ambit of application. In simple terms, it can be understood as a criminal justice procedure to compensate the public in the most direct way possible. It may include tasks like physical labour, bricklaying, digging, assisting NGOs etc. It should first be understood that community sentencing is a payback and should be done in proportion to the crime and in the best-suited place/locality. Initially, community service does appear to be a progressive measure to reform non-serious offenders, yet the application differs. For instance, will the offenders even turn up for work? Will there be crime deterrence? Would the courts simply direct offenders to community service, on the failure of whose compliance there will be more litigation altogether? These are some of the many questions left unanswered by Bills.

Community Service over the years

Justice Charles Solomon, Supervising Judge of the Manhattan Criminal Court stated, “It’s regarded highly by the judges; it’s more meaningful to have someone do two weeks of real work than to sit in a jail cell for two weeks.”[1][i]Indeed it is. But its proper enforcement is the one factor that helps achieve the main goals of this type of sentencing. But even before that could be done, it is of essence to determine if India needs this form of sentencing; if it would be beneficial and not counter intuitive.

The possible problems with Community Sentencing in India can be identified as follows:

1. Unchecked Absenteeism

One of the earliest experiments of community service punishment was done in California in the 1960s for non-serious offenders, but one definitive case was observed in New York in 1979 as a result of the operations of the Community Service Sentencing Project (CSSP).[2][ii] A man named Willie, convicted for theft, was sentenced to community service. But he was absent on the first day itself. All his submitted addresses were apprehended but in vain. It was then found that he was enrolled in a methadone maintenance programme, where he was finally found and then directed to complete his sentence.

[Image Sources: Shutterstock]

Evidently, it was difficult to keep track of absenteeism since the very first day, and the project arguably failed. It is known that it became more effective in the subsequent days, but nevertheless it soon lost its credibility. Here, the attendance of the offender would be of principal significance. But the Sanhitas do not provide any ways to ensure that the offender actually turns up and performs the tasks. Of course, in case of absenteeism, the offender’s residence could be approached. But again, neither are there the forces and mechanisms necessary to apprehend every one of them, nor is there any guarantee of their presence at those places.

Supervision teams can be institutionalised for the above purpose, but for a country with a population like ours, it is simply impractical to have a team that keeps a check on the whereabouts of petty offenders. Not every area in the country can be expected to have adequate resources and suitable people to formulate these teams. Hence, the lack of supervisory mechanisms will obviously result in absenteeism.

Australia follows a system of electronic monitoring by using wearable devices, GPS trackers etc. in case of community supervision sentences.[3] The same could be used in India as well, but the point of debate that would arise here is if there is a need to have such an invasive control over the privacy of a person convicted for a non-serious offence and whether this would violate the principle of proportionality followed in the criminal justice system.

2. Increased cases of illegal affidavit drafting

It is a well-understood fact that there is physically no way of determining the whereabouts of any person without employing a supervisor to keep a watch. But to battle the same, there is little to no clarification from the government about the verification of the completion of service.

In countless cases, this absenteeism would be off the records just because the sentenced offenders would simply present an affidavit representing the completion of their service, which is fairly easy to obtain, since there are thousands of lawyers without cases, just looking for opportunities like these to earn some money.

Consequently, the community service sentence would be served only on record, while in reality, the accused never worked even a day. The Sanhitas aim at reducing the litigation quantitatively and facilitate speedy decisions, but this policy might just end up being counter intuitive in that context. If proper supervision is not done, or if attendance is unchecked, disputes would arise between the offenders and their supervisors, adding on to the existing burden of courts.

The consequences of drafting such illegal affidavits amounts to perjury, as was adjudged by Gujarat High Court in the case of Jayesh kumar Ramanlal Patel v. State of Gujarat (2010)[4][iii]. It was given that under section 191 of the Indian Penal Code 1860, such act of perjury could make the person face imprisonment up to seven years and a fine along with it. In addition to this, such an act of drafting and submission of an illegal/fabricated affidavit is considered a contempt of court, which can result in both civil and criminal contempt proceedings against the person. It is crucial to understand that the legal system of any country places the value of truthfulness and credibility on a very high pedestal, which is regarded while adjudicating cases.

3. Negligible Deterrence

Criminal mentality needs a substantial blow in order to show deterrence. An order mandating just labour work would not have an effect as grave as that of fine and (if applicable) recovery of stolen property, and deterrent enough. It has been found that most petty thieves are drug/alcohol addicts, and they commit the offences for the smallest amounts, just to be able to buy their regular amount of substance.[5][iv] Community service would have more or less no effect on deterrence whatsoever.

In fact, deterrence theory propounds that people don’t commit crime because they are afraid of getting caught. In this case, the offender doesn’t have the fear of paying a hefty fine or being imprisoned for it. Instead, there is only the knowledge that he may have to work at a construction site.

Additionally, it is of immediate matter to understand that Community Service systems are often standardised and not made according to the specific intensity, degree and kind of crime committed by the individual. Without tailoring the executive function of the policy, it will no way be effective in increasing crime deterrence.

Additionally, this also brings in the possibility of further amendments that could be made that extend community service not only for petty offences, but graver offences as well (for instance corporate crimes and white-collar crimes). Given that India is attempting to adopt this idea of community service from foreign nations, the above possibility is not very distant. In the 2014 case of Francis Pasha Dias &Anr. Petitioners v. The State of Maharashtra &Anr.,[6][v] the people convicted of attempt to murder were sentenced for 12 weeks of community service. According to multiple legal scholars worldwide, this so-called punishment to an offence that almost ended someone’s life was said to be highly disproportionate in favour of the convicts. This is exactly what the author attempts to explain. It is understandable that jails are overcrowded, but that does not give courts the liberty to, in a manner of saying, leave such people unpunished. It is agreed that reformation is necessary, but retribution is important as well, especially in case of graver crimes like these.

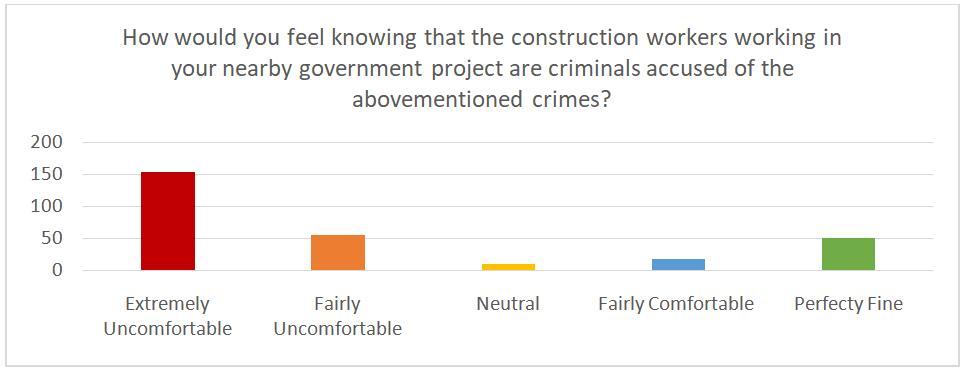

The impact of offenders serving an outdoor punishment can be gauged just by the common sense of our understanding, which brings us to the next problem: Are people completely comfortable with the fact that people working at certain places are actually criminals?

4. Is the public comfortable with criminals working outside?

This new change brings an implication that criminals will be working outside of enclosed premises like jails, and often in full public view. It was found in a survey conducted by the author that 153 out of 267 individuals were “Extremely Uncomfortable” while only 51 were “Perfectly Fine”. In all, 208 were on the uncomfortable side and only 79 did not mind the presence of offenders in public as workers.

This goes on to show that the people themselves do not wish to have criminals working around in public places.

5. A cakewalk for repeat offenders

Unlike fine or short-term incarceration that impose a fear of the direct and immediate consequences of their actions, community service implies the spirit of a delayed punishment, which may not be effective enough to deter crime. Here, it is apt to take the instance of crimes that don’t require a specific criminal intent, for instance, jumping a red light, or not wearing a helmet or a seat belt. Would awarding community service really work for such trivial offences? What about repeat offenders? The Sanhitas do not consider these possibilities at all.

The offenders would believe that these punishments are lenient and not punitive enough to deter crime. Practically, would a petty thief think twice before committing the theft just because he might later be sentenced to watering plants at a government office?

Community Sentencing around the world

- Finland: The ‘happiest country’ is known for its educational and gender-sensitive approach towards community sentencing. The sentencing is done with a focus of teaching the offenders new skills (also Germany) which would help them get employed and hence refrain from committing petty crimes again. The country’s gender-sensitive approach understands the needs and capabilities of every offender before the sentencing is done. Both these approaches have shown great crime deterrence and hence should be considered while codifying the said legislation in India.

- UAE: The form of community sentencing prescribed in the law practised here gives this discourse a religious angle. It is very common for petty offenders to be sentenced to memorize the Holy Quran along with one out of the 19 prescribed services[7][vi], like working at a petrol station, cargo loading/unloading etc. Given that India is a secular country that upholds the value of keeping religion and criminal justice separate, it is obviously not advisable to adopt the first mentioned work. But if India follows the codification aspect of UAE’s system, the sentencing shall be much more judicial. There will be a quantifiable degree on the basis of which the act of the petty offender could be gauged, before being suitably sentenced to perform a particular service.

- South Africa: The system of correctional supervision[8][vii] is very commonly observed in the case of South Africa, in furtherance to the acknowledgement of the fact that punitive measures tend to break families apart. India being a country known for its family values, should consider this option as well in case of petty thievery and such offences.

- New Zealand: The influence of the Maori culture[9][viii] in this region has aided the punishment regime as well. The core values of this culture mainly revolve around the institution and development of culturally-sensitive and community-oriented systems. Indian values hold not much difference from this, and hence they should be considered as well.

- Canada: Canada’s community sentencing includes yet another dimension by actively incorporating the justice traditions[10][ix] followed by its indigenous communities in order to serve all communities better. India’s indigenous communities (For example,Adivasis of Chandrapur, Maharashtra) often face injustice, if not downright discrimination, and application of Canada’s perspective would be very beneficial.

Recommendations: how resolve these fallacies in the Community Service system?

First, the government should release a list of community service acts with their respective proportional offence. This would help create a well-codified law for these offences, since it is against general jurisprudence to leave the entire punishment pronouncement only at the discretion of the particular court. This will eliminate any arbitrariness and subjectivity that might arise in the system. Additionally, the list must contain quantifiable acts that can be measured in both hours and output, and that can be reduced or increased as per the facts and circumstances of every case.

Second, for the new punishment regime to work, a new branch of officers must be constituted under the jurisdiction of every police station (wherever suitable), which will be dedicated to all the supervisory functions. The supervision shall be based on risk-levels with a behavioural-management approach.[11][x]This will not only strengthen the police forces of the country, but will also reduce deterrence, and increase employment as added benefits.

Third, in order to ensure that absenteeism does not foil the plans of this policy, hour-wise attendance should be marked along with signature of the offender, on the basis of which the final affidavit declaring the completion of sentenced hours to be completed.

Fourth, as deriving from justice systems in the USA, Europe, etc., a prescribed uniform should be mandated that expressly shows that they are not just labour/workers but community service. For instance, brightly-coloured Hi-vis safety jackets bearing the words ‘Community Service’ could be worn by such offenders. This way, the general public would be aware that the people they are witnessing to be working are actually offenders.

If all these suggestions are considered, community service may not just remain as ‘tusks’ of law,but ‘teeth’ that would actually have a major substantial and procedural effect on the criminal justice system.

Way forward

Community service is by far one of the best-resulting pathways of reformative justice in the world, but it could prove difficult for enforcement in India due to multiple factors like diversity, region, etc. Not just the enforcement, but also the verification of documents and affidavits would also become less credible, and India cannot afford to lose out on the credibility of its lawyers.

In conclusion, it is apt to state that fear of punishment is one of the principal deterrent factors in delinquency, but in no way is community service punitive enough to deter people from committing crime. The method is admittedly reformative, but has shown to lacks deterrence-induction. Hence, an extremely selective and careful implementation along with the given suggestions would not only assist in reformation, but also in building a better-balanced society.

Author: Swaraj Dongre, a 3rd year law student from Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab, in case of any queries please contact/write back to us via email to chhavi@khuranaandkhurana.com or at Khurana & Khurana, Advocates and IP Attorney.

[1]https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/a/anderson-justice.html

[2]https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/a/anderson-justice.html

[3]Black M & Smith R 2003. Electronic monitoring in the criminal justice system. Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice no. 254. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi254. Accessed 13 October 2023

[4]Jayesh kumar Ramanlal Patel v. State of Gujarat 2010 SCC ONLINE GUJ 13421

[5]Rafaiee, Raheleh et al. “The relationship between the type of crime and drugs in addicted prisoners in zahedan central prison.” International journal of high risk behaviors & addiction vol. 2,3 (2013): 139-40. doi:10.5812/ijhrba.13977, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4070162/.Accessed 2 September 2023

[6]Francis Pasha Dias &Anr. Petitioners v. The State of Maharashtra &Anr. 2014 SCC ONLINE BOM 2777

[7]https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/courts/uae-judges-now-have-19-options-for-community-service-sentences-1.674647

[8]http://www.dcs.gov.za/?page_id=317#:~:text=Correctional%20supervision%20is%20a%20prevent

[9] Juan Tauri “Indigenous perspectives and experiences: Maori and the criminal justice system” Simon Fraser University Press, https://www.sfu.ca/~palys/Tauri%20chapter%20on%20Maori%20the%20CJS.pdf, Accessed 10 October 2023

[10]https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/justice/criminal-justice/bcs-criminal-justice-system/understanding-criminal-justice/indigenous-justice/program_communities

[11]Center on Sentencing and Corrections, Vera Institute of Justice. “The Potential of Community Corrections to Improve Communities and Reduce Incarceration.” Federal Sentencing Reporter, vol. 26, no. 2, 2013, pp. 128–44. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/fsr.2013.26.2.128. Accessed 3 Sept. 2023.

[i]https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/a/anderson-justice.html

[ii]https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/a/anderson-justice.html

[iii]Jayeshkumar Ramanlal Patel v. State of Gujarat 2010 SCC ONLINE GUJ 13421

[iv]Rafaiee, Raheleh et al. “The relationship between the type of crime and drugs in addicted prisoners in zahedan central prison.” International journal of high risk behaviors & addiction vol. 2,3 (2013): 139-40. doi:10.5812/ijhrba.13977, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4070162/. Accessed 2 September 2023

[v]Francis Pasha Dias & Anr. Petitioners v. The State of Maharashtra & Anr. 2014 SCC ONLINE BOM 2777

[vi]https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/courts/uae-judges-now-have-19-options-for-community-service-sentences-1.674647

[vii]http://www.dcs.gov.za/?page_id=317#:~:text=Correctional%20supervision%20is%20a%20prevent

[viii]Juan Tauri “Indigenous perspectives and experiences: Maori and the criminal justice system” Simon Fraser University Press, https://www.sfu.ca/~palys/Tauri%20chapter%20on%20Maori%20the%20CJS.pdf, Accessed 10 October 2023

[ix]https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/justice/criminal-justice/bcs-criminal-justice-system/understanding-criminal-justice/indigenous-justice/program_communities

[x]Center on Sentencing and Corrections, Vera Institute of Justice. “The Potential of Community Corrections to Improve Communities and Reduce Incarceration.” Federal Sentencing Reporter, vol. 26, no. 2, 2013, pp. 128–44. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/fsr.2013.26.2.128. Accessed 3 Sept. 2023.