INTRODUCTION

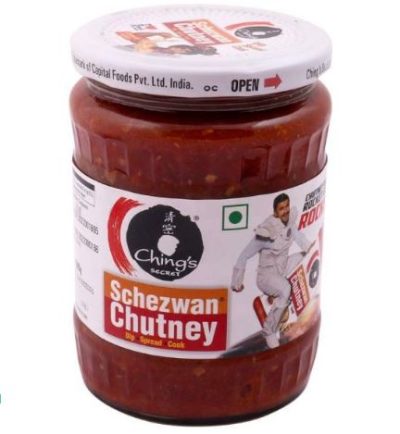

Indians love Chinese food, or, more accurately, Indo-Chinese food; a unique blend of the cuisines and tastes prevalent in the two neighbouring countries that is loved most only by one of them. Perhaps an (abhorrent) frankenstein of sorts to most Chinese people, Indians of all sorts, Mahrashtrians, Kannadigas, Delhiites, and Bengalis – amongst others – find Indo-Chinese cuisine positively delightful. As such, products and foods that can be classified as Indo-Chinese, do rather well with Indian consumers. One such product, therefore, is Ching’s Secret’s Schezwan Chutney, which is a regular Indian chutney, with strong “Desi-Chinese” flavours, blending the pungency of Schezwan and masalas and spices of Indian cooking. Capital Foods Private Limited, the owner of the Ching’s Secret brand also holds the trademark, ‘SCHEZWAN CHUTNEY’. In 2023, a company called Vimal Agro Products Private Limited, that also possessed a similar line of products, also called Schezwan Chutney, filed a petition seeking cancellation of the aforesaid trademark, on the primary contention that the phrase “Schezwan Chutney” is descriptive and generic phrase.

WHAT IS A TRADEMARK?

A trademark, as per Section 2 (1) (zb) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, is a “mark capable of being represented graphically and which is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others and may include shape of goods, their packaging and combination of colours”. Essentially, a trademark is a word, phrase, symbol, that is capable of being used to distinguish the products or services of one entity from another. Such a mark, in Indian Law, can be a signature, name, label, or heading. Furthermore, the Act, in Section 2 (1) (w), defines a

[Image Sources: Shutterstock]

Registered Trade Mark as a mark that is on the registry of trade marks and is in force. The effect of a registered mark, is that the person to whom the registration has been assigned, has exclusive use over such mark, and is the only entity authorised to use such mark, unless such mark has been lawfully assigned to another party.

Trade marks, however, are not permanent and limitless, and generally are required to be renewed after ten years. Additionally, trade marks can even be cancelled, under Section 57 of the Act, and a rectification petition can be filed with either the Registrar, the Appellate Board, or a High Court of the petitioner’s choice. This petition can be filed if an entry was made in the register without sufficient cause, or because the entry was wrongly remaining on the register, or because of any error or defect in the entry in the register

A BRIEF OF THE CASE

Facts giving rise to the case

Ching’s Secret, a brand of the holding company, Capital Foods Private Limited, launched its line of ‘Schezwan Chutney’ in the early 2000s. As such, in 2012, the company applied for registration of the phrase ‘Schezwan Chutney’ as a trade mark of the company, which is iconic in India for its “Desi-Chinese ” line of foods and food related products. The registration so requested was granted, subsequently. Vimal Agro Products Pvt. Ltd., a similarly home grown brand, also launched its line of ‘Schezwan Chutney’, in the early 2000s. Capital Foods, in view of this line of products launched by Vimal Agro, and with the motivation of preventing unauthorised use of its registered trade mark, filed a suit before the District Court, Nashik. Subsequently, Vimal Agro sought leave from the Nashik Court to file a petition for cancellation / rectification before the High Court of Bombay. Subsequent to the grant of leave, however, Vimal Agro, proceeded to file a petition of the aforementioned nature, Under Section 57 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, before the High Court of Delhi, which is the petition that is the subject of the current discussion.

Arguments on behalf of the Petitioner

The Petitioner, seeking cancellation under Section 57 of the Act of the trade mark ‘SCHEZWAN CHUTNEY’, filed the aforesaid petition on two primary grounds;

- That the phrase “schezwan chutney” is a descriptive and generic mark, and therefore the trade mark cannot be given exclusively to Ching’s Secret, as it is well settled law that a descriptive and generic term cannot be trade marked, given that it is highly undesirable that a single entity be granted proprietary rights over a term that is generic and descriptive.

- That the application for registering of the mark was abandoned, by way of the Registrar’s order dated 29th March 2016, due to the fact that the Registrar’s objection to the said trade mark application went unnoticed and unaddressed by the petitioner, in spite of which the said trade mark registration was granted.

Arguments on behalf of the respondent

Respondent No. 1, Capital Foods Private Limited, largely ignoring the contentions and the submissions of the Petitioner, argued before the Hon’ble Court to the effect that the Petitioner, regardless of their contentions, lacked the jurisdiction to approach the Court in the first place, in view of a pending suit on the same matter before the learned Single Nashik District Judge, wherein the Petitioners admitted that the High Court of Bombay would have the sole and exclusive jurisdiction to decide on a rectification petition under Section 57 of the Act, and in fact sought specific leave from the Nashik Court to approach the Bombay High Court, which was granted.

The decision of the High Court of Delhi

The Hon’ble Justice Pratibha M. Singh, speaking for the High Court, largely left the question of whether the trade mark is amenable to being stayed open-ended, and indicated that the Court was not inclined towards answering this aforementioned question at the current juncture, instead choosing to focus on the issue of jurisdiction, stating that this would need to be answered to before any detailed discussion on the validity of the trade mark itself could arise. The matter, thus, is now listed for the consideration of the issue of jurisdiction, for the 21st of February, 2024.

ON THE QUESTION OF VALIDITY

Given – and although – the High Court declined to comment conclusively on the matter of whether the trade mark could be stayed / cancelled, an academic discussion on whether the trade mark could potentially be stayed / cancelled is not unwarranted and would be useful, academically speaking.

Descriptive and generic

With the support of a multitude of precedents of several High Courts and the High Court involved in the current subject matter, it is well settled in law that a mark that is both descriptive and generic is not capable of being a registered mark. As was explicitly and succinctly stated in the case of Consim Info Pvt. Ltd. v. Google India Pvt. Ltd. [2013], a “descriptive mark was a word, picture, or another symbol that directly describes something about the goods or services in connection with which it was used as a mark. Such a term may be descriptive of the desirable characteristics of the goods”. In essence, therefore, a descriptive mark is a mark that hints or explicitly states as to what the product itself is, and what its characteristics, ingredients, and qualities are. It does not, in its descriptive nature, offer a clue as to the source of the product, and does not allow the product in question to be differentiated from products that are of different sources.

This classification of a mark is not only by virtue of precedent disallowed from being registered and made an entry in the registry, but also by legislation, specifically Section 9 (1) (a) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, which lays out that a trade mark shall not be registered if they are trademarks –

“(a) which are devoid of any distinctive character, that is to say, not capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of another person”.

The question, for the purposes of this discussion, therefore, is whether the phrase ‘Schezwan Chutney’ is descriptive and generic, and whether it distinguishes the Schezwan Chutney of Capital Foods from the Schezwan Chutneys of other brands.

On that note, Schezwan Chutney, as a term is a direct description of the product as being a condiment, and of the flavours one can expect from the product, which are a blend of the pungent flavours originating from the Sichuan region of China (indicated by the word Schezwan), and masalas, flavours, and spices inspired by Indian tastes (which is indicated by the term Chutney). Most consumers, clearly, through the phrase ‘Schezwan Chutney’ will understand that the product is a pungent, slightly sour, spicy condiment that is full of masalas, and is made up of, at the very least, chillies, garlic, and various spices. The word chutney, additionally, also indicates that the condiment will not be smooth and hyper-processed, but might be in fact chunky in nature. The term in question, therefore, directly leads the consumer to the ingredients, qualities, and characteristics of the condiment.

A registered trade mark typically answers the questions of ‘Who are you? Who vouches for you? Where do you come from?’,but the generic product name and mark only answers the question of ‘what are you?’. The mark at hand, therefore, only answers the question as to what the product is, and is not in any way indicative of the source of the product, especially in view of the fact that there are currently 9+ brands that also sell schezwan chutney. It is not, in that regard, the phrase / mark “schezwan chutney” that is the distinguishing factor, but rather the brand name that the schezwan chutney will be sold under. The mark, therefore, given that it makes a direct reference to the quality and nature of the product, is generic, as well as descriptive.

Furthermore, the Delhi High Court, in the case of Capital Foods Private Limited v Radius Indus Chemical Private Limited, prima facie found that the phrase ‘schezwan chutney’ is descriptive and generic, and does not speak to the source or the origin of the product, and does not aid the consumer in distinguishing the schezwan chutney of one brand from the chutney of another brand.

Secondary meaning

A mark being descriptive and generic is not the end of the world, and such marks can be saved if they acquire what is termed as secondary significance or secondary meaning. Essentially, it will be saved from the provisions of Section 9 if it has acquired distinctiveness through secondary meaning. This means that a mark may be deemed to distinctive if the mark has become largely recognisable in the public domain as one standing for goods from a particular source, that is; a situation where the mark and the product have become synonymous with the source / origin of the product. A situation of this nature cannot be proven by mere sales figures (as was held in IHHR Hospitality Pvt. Ltd. v. Bestech India Pvt. Ltd.), which Capital Goods has attempted to do in a plethora of cases. Such a situation, at least in this case, cannot be proven conclusively, especially in the light of the fact that, as the court recognised in Capital Foods Private Limited v Radius Indus Chemical Private Limited, there exist dozens of brands and firms selling products labelled as Schezwan Chutney. When there exists such a large inflow of firms selling products labelled the same as the impugned product and mark, and especially when such firms and products have largely been introduced in the early years of Ching’s Secret’s Schezwan Chutney, it would be difficult to conclusively prove a status of synonymity between the mark and the source of the product bearing the mark.

A great example of a mark acquiring secondary meaning, is the trade mark ‘Apple’ as in the US based smartphone (and other devices) giant, which, although in ordinary meaning only refers to the fruit, has acquired such status to the effect that the expression ‘Apple’ no longer merely means what it used to, and at least the second thought that occurs to any ordinary user when hearing the expression ‘Apple’, is the smartphone giant. The firm in this case, Ching’s Secret, therefore, has not acquired such a secondary meaning for its mark, that is; Schezwan Chutney.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Therefore, despite the Court in the present case having not delved into the aspects of the validity, or at least not seriously considering the issue seriously – as the issue of jurisdiction must first be resolved – it is clear, at least in the opinion of this author, that the impugned trade mark would not be valid, and would amount to conferring sole proprietary rights over an expression of common usage, and would amount to granting a monopoly over the expression when it is very clearly an expression of a descriptive and generic nature, which has not yet attained the status of secondary meaning. The registration of the mark, therefore, may be liable to be cancelled, in view of the arguments and reasonings presented above.

Author: Neil Patwardhan, A Student at at the National Law Institute University, Bhopal, in case of any queries please contact/write back to us via email to chhavi@khuranaandkhurana.com or at Khurana & Khurana, Advocates and IP Attorney.

REFERENCES

Case laws

- Vimal Agro Products Pvt. Ltd. v Capital Foods Pvt. Ltd. &Anr.

C.O. (COMM.IPD-TM) 227/2023

- Capital Foods Pvt. Ltd. v Radiant Indus ChemPvt. Ltd

2023 SCC OnLine Del 118

- IHHR Hospitality Pvt. Ltd. v. Bestech India Pvt. Ltd.

2012 SCC OnLine Del 2713

- Consim Info Pvt. Ltd. v. Google India Pvt. Ltd.

2013 (54) PTC 578 (Mad)

Statutes

The Trade Marks Act, 1999.

Online websites

- Editor_4, Delhi High Court refuses to stay the registration for the mark ‘SCHEZWAN CHUTNEY’ (SCC Blog, 17 October 2023) <https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/10/17/delhi-hc-refuses-to-stay-the-registration-for-the-mark-schezwan-chutney-legal-news/> Accessed 19 October, 2023.

- Debby Jain, Delhi High Court Refuses To Stay Ching’s Trade Mark Registration For “Schezwan Chutney” (LiveLaw, 17 October 2023) <https://www.livelaw.in/high-court/delhi-high-court/delhi-high-court-refuses-stay-ching-schezwan-chutney-trademark-registration-240362> Accessed 18 October 2023

- Express News Service, ‘Schezwan chutney merely descriptive term’: Delhi HC nixes trademark infringement claim of Chings ‘Schezwan Chutney’ (Indian Express, 14 January 2023) <https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/schezwan-chutney-merely-descriptive-term-delhi-hc-nixes-trademark-infringement-claim-of-chings-schezwan-chutney-8381242/> Accessed 18 October 2023

- ParinaKatyal, ‘Schezwan Chutney’ Descriptive Of Quality: Delhi High Court Rejects Capital Foods’ Plea For Interim Injunction Against Alleged Trademark Infringement (LiveLaw, 13 January 2023) <https://www.livelaw.in/news-updates/schezwan-chutney-descriptive-of-quality-delhi-high-court-218912?infinitescroll=1> Accessed 18 October 2023

- Sana Singh, Trademark Law in India – Types of Trademarks, Registration Procedure and Acquired Distinctiveness of Generic Words (Singhania& Partners Blog, 21 September 2021) <https://singhania.in/blog/trademark-law-in-india-types-of-trademarks-registration-procedure-and-acquired-distinctiveness-of-generic-words> Accessed 19 October 2023

- Anonymous, Trademark Act, 1999 (ClearTax, 10 May 2022) <https://cleartax.in/s/trademark-act-1999> Accessed 18 October 2023

- Anonymous, Trademark Rectification in India (S.S. Rana& Co. Blog, unknown) <https://ssrana.in/ip-laws/trademarks-in-india/trademark-rectification-india/#:~:text=Section%2057%20of%20the%20Trade,the%20registration%20of%20the%20trademark.> Accessed 19 October 2023

- UrfeeRoomi, Janaki Arun, Ayush Dixit, Jurisdiction for Trademark Cancellation Petitions: Aftermath of The Tribunal Reforms Act, 2021 (Bar & Bench, 29 March 2023) <https://www.barandbench.com/law-firms/view-point/jurisdiction-for-trademark-cancellation-petitions-aftermath-of-the-tribunal-reforms-act-2021#:~:text=Under%20the%20TM%20Act%2C%20as,which%20Registry%20or%20High%20Court.> Accessed 19 October 2023

- Manisha Singh, India: Distinctiveness through Secondary Meaning (Mondaq, 25 April 2006) <https://www.mondaq.com/india/trademark/39320/distinctiveness-through-secondary-meaning> Accessed 18 October 2023