Introduction

The dispute between Adidas and Skechers is a keynote example to depict the multifaceted perspectives regarding the impact, application, and importance of a Trademark in the business realm.

A trademark is one which possesses the power to differentiate & attribute goods/services of a firm from the other players in the market whose registration is not compulsory. It provides the creator/owner a sense of security & reward for their creation and grants the right to utilize the mark in the operation of the firm and prohibits or prevents other parties from creating/using similar words, phrases or images that would distort the reputation of the original and create a sense of ambiguity among the customers.

Adidas and Skechers are key players in the athletic footwear & apparel market who have competed for a long time in various aspects in their course of business.

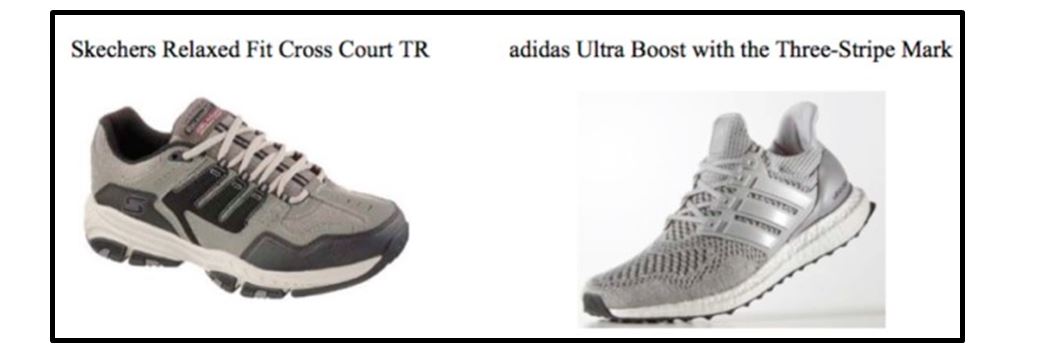

This case revolves around the similarity in the design and the features of the Skechers Onix Shoe with the famous Adidas Stan Smith Shoe. Also, the Three Stripe mark which identified Adidas in the market played a major role in its marketing & branding approach which eased the customers’ ability to identify Adidas and its original products with ease through the Three Stripe mark. The dispute arose when it was alleged by the Plaintiff that the defendant’s Relaxed Fit Cross Court TR shoe contained a pattern which violated and imputed the three Stripe Mark and its reputation.

SLEEKCRAFT FACTORS

The United States Courts for the Ninth Circuit has put forward a multi-faceted trademark infringement & confusion analysis test under 15 U.S.C. §§ 1114(1) and 1125(a) known as the Sleekcraft factors test to understand “whether the defendant’s use of the trademark is likely to cause confusion about the source of the plaintiff or the defendant’s goods.” Also known as the likelihood of confusion test, it plays a significant role deciding whether the average consumer would believe that the product of an infringer had a link with the plaintiff’s product.

The case of AMF Inc. v. Sleekcraft Boats (1979)[1] was the initiation point for the Sleekcraft factors test which was developed & applied by the Ninth Circuit to solve the likelihood of confusion in the above mentioned case. “SLICKCRAFT” was a trademark filed & registered by the plaintiff who was a manufacturer of boats. The defendant, who was also a boat manufacturer utilized the name “SLEECKCRAFT in its company logo as the defendant had no prior knowledge of the plaintiff or their registered mark. Plaintiff filed a trademark infringement suit against the defendant describing the likelihood of confusion among the consumers and in the industry market. The U.S. District Court for the Central District of California stated that the “simultaneous use of the two marks was unlikely to confuse the public”.

[Image Sources : Shutterstock]

The matter was appealed before the Ninth Circuit which analyzed the likelihood of confusion among the public and the result portrayed the fact that both parties were similar similar goods but are not competitive. The Sleekcraft Court (Ninth Circuit) also found that both partied dealt with similar products but catered to different target markets. The AMF boats were utilized by family audiences whereas Sleekcraft boats were used in high speed recreations. The Circuit relied in hard evidence as they felt a sense of difficulty in resolving the confusion.

Hence, the Circuit court discovered a higher probability for a future competitive scenario and thus, provided the plaintiff with the “greater protection” of its mark. The Circuit court held that the application of the Sleekcraft factors played an important part in favoring the ruling for the plaintiff and issue an injunction to mention the appropriate relief.

The following are the Sleekcraft factors:

- Strength or Weakness of the Plaintiff’s Mark

- Defendant’s Use of the Mark

- Similarity of Plaintiff’s and Defendant’s Marks

- Actual Confusion

- Defendant’s Intent

- Marketing/Advertising Channels

- Consumer’s Degree of Care

- Product Line Expansion

Analysis

According to Bloomberg[2], the global footwear market will attain a positive & enormous capacity of approximately $626,164 million by 2030. In the present global footwear market, the US is the leading revenue generator across the globe with around $88 billion as of 2023 with players like Adidas America Inc., Skechers USA Inc., Crocs Retail, LLC and Nike Inc. competing to be the market leader of the US footwear industry.

This case can be viewed in 2 angles:

- Adidas’s Stan Smith Shoe and Skechers’s Onix Shoe – Dilution of Unregistered Trade Dress Dispute

In the 1970s, Adidas released a shoe titled Stan Smith which went on to become a great success & was largely popular among the consumers. It also featured in the Wall Street Journal and received the ‘Shoe of the Year’ award in 2014. On September 14, 2015, Adidas filed a suit against Skechers stating that the Skechers Onix shoe contains a similar feature as that of the Stan Smith shoe and has indirectly distorted the the unregistered trade dress of the Adidas Stan Smith shoe.

“Trade dress protection applies to `a combination of any elements in which a product is presented to a buyer,’ including the shape of the product.”[3]

The matter was deliberated through a different perspective which dealt with the various forms of capital resources, human labour, celebrity endorsements, etc involved to ensure that the Adidas’s Stan Smith attains the ‘iconic status’ and hence acquires a secondary meaning among the consumer market. On the other hand, the attachment of metadata tags by Skechers on its website to direct the customers surfing the internet for the Adidas Stan Smith Shoe to its Onix Shoe can be linked with this ruling “Using another’s trademark in one’s metatags is much like posting a sign with another’s trademark in front of one’s store.”[4]

To prove that Adidas has faced irreparable harm from the Onix shoe, the company put forward its promotional efforts & campaigns, product placement to ensure the promotion of the Stan Smith shoe and its customer surveys to put forward the consumer market situation where close to 20% of the customers believed that the Skechers Onix was produced & marketed by Adidas which depicts the presence of confusion & ambiguity among the customers.

The likelihood of confusion in the concerned trade dress is analyzed through the application of the Sleekcraft factors in the general context of trademarks. There exists a major nexus between this case and the first Sleekcraft factor which is “the greater the similarity between the two marks at issue, the greater the likelihood of confusion”. The following are the key similarities between the Stan Smith and the Onix:

- White leather in the upper region

- Raised Green mustache shaped heel path

- Perforations with angular stripes

- Similar stitching pattern around the perforations

- Flat white rubber outsole

The main difference is the use of the Skechers logo in the Onix shoe.

Image Source – Fashion Network, The Fashion Docket

The Court constituted that the filing of the preliminary injunction by Adidas was not erronous in nature after studying the likelihood of success in the merits and the likelihood of irreparable harm which ultimately favoured Adidas to secure its reputation, intangible benefits and brand dynamics in the market.

- Adidas’s Three Stripe mark and Skechers’s Relaxed Fit Cross Court TR shoe – Infringement & Dilution of Adidas Three Stripe mark Dispute

The next part of this dispute deals with the aspect of whether the Cross Court shoe infringes the renowned Three Stripe mark of Adidas and its related designs.

In the course of hearing of the dispute, the Court commented that there seems to be a “likelihood of success on the merits” on the claims of dilution & infringement by Skechers which was later challenged although Skechers accepted the ownership of Three Stripe mark by Adidas.

The Court based its legal analysis on the following key distinctions between the Three Stripe mark and the Cross Court shoe:

- Variance in the thickness of the stripes

- Presence of a strip between the three stripes in the Cross Court

- Length of the stripes did not reach the shoe’s sole

Image Source – Washington Journal of Law, Technology & Arts

As part of its legal analysis, it decided to set aside these difference in their decision making process and held that Skechers and Adidas have had a history of trademark infringement suits and litigations, hence Skechers was aware regarding the ownership of the Three Stripe mark by Adidas during the process of development of the Skechers Cross Court shoe.

In the Brookfield Communications case[5], it was stated that “Evidence of substantial advertising expenditures can transform a suggestive mark into a strong mark”. Thus, it can be inferred that the Three Stripe mark holds the combination of commercial and conceptual strength as it is a well-recognised brand in the marketplace and possesses a distinctive mark & design.

The Court discovered that the “likelihood of success on the merits” was on the side of Adidas as Skechers held the knowledge regarding the Three Stripe mark by Adidas which inferred the objective of Skechers to circumvent the customers regarding the “source of the shoe” by including a similar mark.

The prominent case of Nissan Motor Co. V. Nissan Compt. Corp[6] held that “Dilution is `the lessening of the capacity of a famous mark to identify and distinguish goods or services, regardless of the presence or absence of — (1) competition between the owner of the famous mark and other parties, or (2) likelihood of confusion, mistake, or deception.”

One of the key arguments of Skechers was based on the deficiency of Adidas to produce the required evidence regarding the ownership & the recognition of the Three Stripe mark was considered baseless by the Court owing to the high degree of recognition in the marketplace.

Also in Jada Toys, Inc. V. Mattel Inc.[7], the factors to establish dilution by the plaintiff were stated:

- The mark is famous and distinctive

- The defendant is making use of the mark in commerce

- The defendant’s use began after the mark became famous

- The defendant’s use of the mark is likely to cause dilution by blurring or dilution by tarnishment.

The next argument made by Skechers was that the Court misused its discretionary power during the issue of a preliminary injunction as Adidas had not produced evidence to depict the possible irreparable harm caused due to the sale of the Cross Court shoe. On the other hand, Adidas argued that Skechers distorted their ability to utilize its brand image as there are chances of connecting the Three Stripe mark & Adidas to the “low quality” Cross Court shoes of Skechers. The finding of the Court that Skechers is seen as a “value brand” is an unsupported & conclusory statement as there is no strong basis derivable from the evidence put forward by Adidas.

A key point portrayed in the Court was the conflict between the theory of harm & the theory of customer confusion put forward by Adidas as there was no argument made that a Cross Court shoe purchaser would misinterpret that the shoes of Adidas was purchased by the customer. Such an argument cannot be made as the Cross Court shoe contains multiple references of the Skechers logo & identifying features, but Adidas argues that after the sale, a person looking at the shoe from a long distance or pass by might not see the Skechers logo and thus, there is a possibility of misinterpreting that the shoe is from Adidas.

The status of a ‘premium brand’ does not lost or diluted in any manner even if the consumers undergo a sense of confusion and hence the likelihood of irreparable harm being caused cannot be subjected to assumption. Adidas could not provide valid evidence to prove their claim and hence failed to prove their stance in this argument.

CONCLUSION:

The decision given by the United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit in this case is welcomed as one of the landmark judgements on the topic of Trademark infringements in the modern business-tech world.

Adidas submitted evidence to prove that its goodwill & reputation faced the likelihood of irreparable harm by the Onix shoe of Skechers based on the marketing, supply chain procedures & frameworks employed by Adidas for the sale of the Stan Smith Shoe. Also, the post-sale consumer confusion theory of Adidas proved to harm/distort its “premium brand” status was developed from the exclusivity of the Stan Smith “brand”.

In Playboy Enters v. Netscape Communications Corp.[8] (2004), it was held that “the commercialization of the Internet and, more specifically metatagging and keying, have imposed a new burden on courts and may lead to the constitution of trademark infringements. In this case, the Court tried to reconcile the issues between conventional trademark infringement and “newly emerging technology” related trademark infringements. Such technological advancements reduces the scope for the rigid application of the Sleekcraft test and guiding factors by Courts and hence, it requires a “flexible” utilization of the eight Sleekcraft factors along with the analysis of the concerned evidence & documents.

On the other hand, the claim of Adidas suffering irreparable harm because of the Skechers Cross Court could not be proved due to the inability of Adidas to submit evidence for the same.

The World Intellectual Property Organization commented on the judgement passed in this case by agreeing to the preliminary injunction order passed by the District Court related to the Onix as it was distorting & causing irreparable harm to the famous trade dress of Stan Smith. On the other hand, as Adidas failed in submitting evidence to prove its argument of the likelihood of irreparable harm being caused to the Three-stripe mark of Adidas, WIPO would reverse the preliminary injunction passed on the Cross Court shoe and to conclude, it mentioned that the appeal costs must be taken care by the parties.

Author: B. Sanjit Ram – Student Of Vit School Of Law, Chennai, in case of any queries please contact/write back to us via email to chhavi@khuranaandkhurana.com or at Khurana & Khurana, Advocates and IP Attorney.

AFFIRMED IN PART, REVERSED IN PART

REFERENCES

https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/text/581679

[1] AMF, Inc. v. Sleekcraft Boats, 599 F.2d 341, 347 (9th Cir. 1979)

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/press-releases/2023-01-31/footwear-market-is-forecasted-to-reach-nearly-usd-626-164-40-million-by-2030-size-share-trends-business-development

[3] Art Attacks Ink, LLC v. MGA Entertainment Inc., 581 F.3d 1138, 1145 (9th Cir. 2009)

[4] Brookfield Communications Inc. V. West Coast Entertainment Corp., 174 F.3d 1036, 1064 (9th Cir. 1999)

[5] Brookfield Communications Inc. V. West Coast Entertainment Corp., 174 F.3d 1036, 1064 (9th Cir. 1999)

[6] Nissan Motor Co. v. Nissan Compt. Corp., 378 F.3d 1002, 1011 (9th Cir. 2004)

[7] Jada Toys, Inc. v. Mattel, Inc., 518 F.3d 628, 634 (9th Cir. 2008)

[8] Playboy Enterprises, Inc. v. Netscape Communications Corp., 354 F.3d 1020 (9th Cir. 2004)