- AI

- Air Pollution

- Arbitration

- Asia

- Automobile

- Bangladesh

- Banking

- Biodiversity

- Biological Inventions

- bLAWgathon

- Brand Valuation

- Business

- Celebrity Rights

- Company Act

- Company Law

- Competition Law

- Constitutional Law

- Consumer Law

- Consumer Protection Authority

- Copyright

- Copyright Infringement

- Copyright Litigation

- Corporate Law

- Counterfeiting

- Covid

- Cybersquatting

- Design

- Digital Media

- Digital Right Management

- Dispute

- Educational Conferences/ Seminar

- Environment Law Practice

- ESIC Act

- EX-Parte

- Farmer Right

- Fashion Law

- FDI

- FERs

- Foreign filing license

- Foreign Law

- Gaming Industry

- GDPR

- Geographical Indication (GI)

- GIg Economy

- Hi Tech Patent Commercialisation

- Hi Tech Patent Litigation

- IBC

- India

- Indian Contract Act

- Indonesia

- Intellectual Property

- Intellectual Property Protection

- IP Commercialization

- IP Licensing

- IP Litigation

- IP Practice in India

- IPAB

- IPAB Decisions

- IT Act

- IVF technique

- Judiciary

- Khadi Industries

- labour Law

- Legal Case

- Legal Issues

- Lex Causae

- Licensing

- Live-in relationships

- Lok Sabha Bill

- Marriage Act

- Maternity Benefit Act

- Media & Entertainment Law

- Mediation Act

- Member of Parliament

- Mergers & Acquisition

- Myanmar

- NCLT

- NEPAL

- News & Updates

- Non-Disclosure Agreement

- Online Gaming

- Patent Act

- Patent Commercialisation

- Patent Fess

- Patent Filing

- patent infringement

- Patent Licensing

- Patent Litigation

- Patent Marketing

- Patent Opposition

- Patent Rule Amendment

- Patents

- Personality rights

- pharma

- Pharma- biotech- Patent Commercialisation

- Pharma/Biotech Patent Litigations

- Pollution

- Posh Act

- Protection of SMEs

- RERA

- Sarfaesi Act

- Section 3(D)

- Signapore

- Social Media

- Sports Law

- Stamp Duty

- Stock Exchange

- Surrogacy in India

- TAX

- Technology

- Telecom Law

- Telecommunications

- Thailand

- Trademark

- Trademark Infringement

- Trademark Litigation

- Trademark Registration in Foreign

- Traditional Knowledge

- UAE

- Uncategorized

- USPTO

- Vietnam

- WIPO

- Women Empower

Introduction

“Labor is prior to, and independent of, capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.”

– Abraham Lincoln

Labour has always been significant and accounted for productivity and output, as they have contributed towards the objective. In common parlance, Labour Law serves its title, as also known as Employment Law. In other words, tis’ a body of laws that is based on administrative ruling, precedents that directs the legal rights and obligations of workers, union members and employers in workspace. The Statute acts as guideline to facilitate the aspects of relationship between trade unions, employers, and employees.

Labour Law essentially is divided into two categories

- Collective Labour Law – Relationship between Employer, Employee and Union.

- Individual Labour Law – Employees’ Right to Work and Contractual binding work.

Among the tripartite relationship, the most co-ordinated set is between employer and employee. However, it is not always that it runs smoothly and everything is in place and order. Thus, in times of clashes or conflict between the two the work environment gets affected. It is important that such conflict to be resolved soon for the interest of the workplace. In contrary, strike and lockouts are used as armoury weapons in the hands of the workers and employers. Workers’ ability to go on strike in order to air their complaints and, ideally, the right to strike is misunderstood to be ordinary right. It is often recognized under right to protest provided in Article 19 of Constitution of India, but Right to Strike is not addressed as a fundamental right rather regarded as a Legal Right provided under Industrial Dispute Act, 1947.

[Image Sources : Shutterstock]

Misuse or Means of Strikes and Lockouts is the perspectives resorted to be dealt with. This Research Paper will give an insight to Vires of strikes and lockouts and application of definitions in cases. It will be followed by a ‘Critical Analysis’ which will observe and deliberate upon the Judicial precedents in Indian context. The discussion facilitated under the Critical Analysis will be summed up under Conclusion and Recommendations will be provided in the interest of existing situation and driven principles.

Definition

In words of Ludwig Teller, the word ‘strike’ in its broad connotation has reference to a dispute between an employer and his workers, in the course of which, there is concerned suspension of employment.

According to Section 2(q) of Industrial Dispute Act, 1947 defines: ‘Strike’ means a cessation of work by a body of persons employed in any industry, acting in combination or a concerted refusal or a refusal under a common understanding, of any number of persons who are have been so employed, to continue to work or to accept employment.[1]

After a cursory reading of these definitions, it should be clear that there is a coordinated stoppage of work by a group of employees who share a common understanding of discontinuance during regular business hours. The tenets of definition have been subjected to interpretation by the courts, tribunals, and Supreme Court as well. The Indian judiciary on several accounts has interpreted the strike situation due to inadequate and inapt statutory definition of strike. It has been noted that the existing confusion is largely the result of hazy definitions, a lack of familiarity with the realities of industrial life, and a lack of a policy-oriented approach.[2] However, the main component of the strike has been held that there need not be full-fledged meeting, it could also be a situation wherein a substantial number of workers under an understanding of concert refuse to work for the employer.[3]

“Lockout” has been denied under Section 2(1) of Industrial Dispute Act, 1947 to mean the closing of a place of employment, or the suspension of work, or the refusal by an employer to continue to employ any number of persons employed by him.[4]

The employer reversely plays lockout, whereby he shuts down the workplace on account of threat of punishment or coercion to exert pressure on workers in order to get his way.

Justice Gajendragadkar once said[5]:

“Lockout can be described as the antithesis of a strike. Just as a strikes is a weapon available to the employees their industrial demands. In the struggle between capital and labour the weapon of strike is available labour and is often used by It, so is the weapon of lock out available to the employer and can be used by him. The use of both the weapons by the respective parties must, however, be subject to the relevant provisions of the Industrial Disputes Act.”

Critical Analysis

Under the Act, it assesses the terms ‘strike and lockout’ as supplement to each other. Strike is construed to be an efficacious weapon used by workers to put forth the collective bargaining. Whereas the lockout is role played by the employer mainly for a response to a strike or disputes between workers and managers.[6] The law made for strike is likewise applicable to the lockouts. In other words, an illegal strike followed by a lockout renders the lockout legal and vice versa.

In the case of Shri Ramchandra Spinning Mills v. State of Madras,[7] the court held that the if the employer shuts down the place of business as means of reprisal or an instrument of coercion or as a mode of exerting pressure on the employees or generally when his act is what may be called an act of belligerency there would be a lockout

Right to Strike

In All India Bank Employees Association v. National Industrial Tribunal[8], Supreme Court noted that liberal interpretation of Art. 19(1)(c) cannot be subjected to be granted of the right to strike, either from collective bargaining or otherwise. Thus, the right to strike has no recognition in law moreover the right to form association or Labour union is enshrined.

However, corollary under Industrial Disputes Act, the right to strike and lockout is not absolute in view of the restrictions placed on them provided under Section 10(3), 10-A(4-A), 22 and 23. Thus, the judicial and quasi-judicial decisions have often led to defining the circumstances under which a strike is considered to be legal with some conditions.

Legality Of Strikes And Lockouts

Strikes are often left uncategorised in terms of legality. The law does not clearly emancipate on the same. In accordance with Section 22 and 23 of Industrial Dispute Act, 1947, it is clear that strikes and lockouts are not always illegal.

Labour Appellate Tribunal in the case of Ram Krishna Iron Foundry v. Their Workers[9] explained that the statutory right to strike was enunciated with the aim of regulating it. As observed in another case of G R S M (W) Co Ltd v. District Collector,[10] Kerala High Court summarised the entire situation of strike in simplest words and said that every strike is not illegal and workers may resort to strike in order to redress their grievance or to make certain demands.

To the question that if the constitutional provision in question imposes any limitations on the right in question that are not narrowly tailored to serve the public interest, then the guarantee will have been violated. Andhra Pradesh High Court answered negatively and held that right to lock out is settled to be a statutory right governed and conformed by the relevant provisions of the Act.[11]

Categorization Under The Act

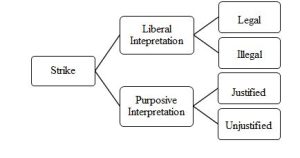

Unlike America or UK, terms such as protected, unprotected, economic and unfair labour practicrs are not so acknowledged in India. To give the Indian context, the Act has classified in terms of Legal and Illegal. Statutory Provisions such as Section 10(3), 10-A(4-A), 22 and 23 are delineated as ‘Illegal Strikes”, in contrary to what doesn’t constitute violative are “Legal Strikes”.[12] The question of legality is dependent on whether the situation has complied and conformed with the aforesaid provisions. Furthermore, in light of purposive interpretation Supreme Court devised Justified and Unjustified categories. Justified strikes is when purported with labour dispute or against any unfair labour practice and could only be resorted with remedies provided by the statutory mechanisms. On the other hand, Unjustified strikes is when workers did not resort with interventions of statutory remedies or in cases their demands been unreasonably high or not in good faith.[13]

Conclusion

Strike, however not a fundamental right in India it is yet a lawful right with statutory immunity reserved for regular workers over the capital class to safeguard their interests and have their complaints redressed. However, strike is a real and undeniable weapon in the hands of the work class, reckless and illegally use of this weapon should not be empowered, as it is hindrance to tranquility of the ventures. Right to strike is a contingent or qualified right just accessible after satisfaction of certain pre-condition. Based with the understanding that the option to go on strike has not explicitly been presented under the Article 19(1) (c) of the Constitution of India. We can presume that option to strike is certainly not a key right grantee to the residents of India, rather it is a legitimate legal right on which the Modern Questions Act, 1947, forces statutory limitations, which in the event that not followed would fall back on illegality aspects, which is punishable under the arrangements of the Act.

Recommendation

- The interpretative application of the courts to categorise the concept of strikes is often misleading. Thus, when the court classify that such action falls both in illegal and justified or other way round like legal and unjustified, the punishment inflicted is subjected on different parameters. In uniformity, the strikes should have been decisive case for violative reasons only.

- It is evident that not every strike situation could be foreseen to prevent the repercussions. However, strike ballot provision remains absent from the Act and such absence results into misuse of strike system. Therefore, it is necessary to bring up the regulation so as to prevent any workmen use the means of strikes in public utility services as provided under Industrial Relations Bill, 1978.

Author: Aditi Borkar, 4th Year student at Symbiosis Law School, Pune, in case of any queries please contact/write back to us via email to chhavi@khuranaandkhurana.com or at Khurana & Khurana, Advocates and IP Attorney.

[12] Syndicate Bank v. Umesh Nayak, 1994 II LLJ 836 (SC).

[13] India Marine Service (P) Ltd v. Workmen, AIR 1963 SC 528.

[6] G.M. Kothari, Labour Demands and Their Adjudication, pp.200-202.

[7] AIR 1956 Mad 241.

[8] 1962 SCR (3) 269.

[9] (1954) 2 LLJ 372.

[10] (1968) 1 W.R 155.

[11] A P Electrical Equipment Corporation v. Its Staff Union, 1986 Lab I.C. 1851.

[1] Section 2(q) of Industrial Dispute Act, 1947.

[2] Shamnagar Jute Dactory v. Their Worknmen (1950) 1 LLJ 0235 (I.T).

[3] Patiala Cement Co. Ltd v. Certain Workers, (1995) 2 LLJ 57 (LAT, Lucknow).

[4] Section 2(1) of Industrial Dispute Act, 1947.

[5] Management of Kairbetta Estate v. Rajamanickam, 1960 AIR 893.