- AI

- Air Pollution

- Arbitration

- Asia

- Automobile

- Bangladesh

- Banking

- Biodiversity

- Biological Inventions

- bLAWgathon

- Brand Valuation

- Business

- Celebrity Rights

- Company Act

- Company Law

- Competition Law

- Constitutional Law

- Consumer Law

- Consumer Protection Authority

- Copyright

- Copyright Infringement

- Copyright Litigation

- Corporate Law

- Counterfeiting

- Covid

- Cybersquatting

- Design

- Digital Media

- Digital Right Management

- Dispute

- Educational Conferences/ Seminar

- Environment Law Practice

- ESIC Act

- EX-Parte

- Farmer Right

- Fashion Law

- FDI

- FERs

- Foreign filing license

- Foreign Law

- Gaming Industry

- GDPR

- Geographical Indication (GI)

- GIg Economy

- Hi Tech Patent Commercialisation

- Hi Tech Patent Litigation

- IBC

- India

- Indian Contract Act

- Indonesia

- Intellectual Property

- Intellectual Property Protection

- IP Commercialization

- IP Licensing

- IP Litigation

- IP Practice in India

- IPAB

- IPAB Decisions

- IT Act

- IVF technique

- Judiciary

- Khadi Industries

- labour Law

- Legal Case

- Legal Issues

- Lex Causae

- Licensing

- Live-in relationships

- Lok Sabha Bill

- Marriage Act

- Maternity Benefit Act

- Media & Entertainment Law

- Mediation Act

- Member of Parliament

- Mergers & Acquisition

- Myanmar

- NCLT

- NEPAL

- News & Updates

- Non-Disclosure Agreement

- Online Gaming

- Patent Act

- Patent Commercialisation

- Patent Fess

- Patent Filing

- patent infringement

- Patent Licensing

- Patent Litigation

- Patent Marketing

- Patent Opposition

- Patent Rule Amendment

- Patents

- Personality rights

- pharma

- Pharma- biotech- Patent Commercialisation

- Pharma/Biotech Patent Litigations

- Pollution

- Posh Act

- Protection of SMEs

- RERA

- Sarfaesi Act

- Section 3(D)

- Signapore

- Social Media

- Sports Law

- Stamp Duty

- Stock Exchange

- Surrogacy in India

- TAX

- Technology

- Telecom Law

- Telecommunications

- Thailand

- Trademark

- Trademark Infringement

- Trademark Litigation

- Trademark Registration in Foreign

- Traditional Knowledge

- UAE

- Uncategorized

- USPTO

- Vietnam

- WIPO

- Women Empower

Kim Kardashian West, the popular American media personality, described by her critics and admirers as being ‘famous for being famous’ was recently in news this June after receiving a wave of backlash on social media against the decision to name her new shapewear line “Kimono” which is also a traditional Japanese robe garment.

The issue is related to Kim’s lingerie brand, KIMONO-a new line of shapewear and the wider problem of fashion’s cultural appropriation. The brand website explains that Kimono is “a new, solution-focused approach to shape-enhancing underwear” and “fueled by her (Kim’s) passion to create truly considered and

highly technical solutions for everybody”. The name of the brand is obviously a clever (some would say deliberately inventive) play on words with Kardashian’s first name, but a huge uproar has erupted online with regards to the fact that the brand is named after the traditional Japanese garment, the venerable ‘Kimono’. Following the launch of her brand, Kardashian came under public outrage, both in America and Japan and primarily on social media platforms labeling it as “cultural appropriation” with people expressing their dissatisfaction and disapproval with the fact that the so-called shapewear Kardashian shared in photo promos looks nothing like an actual ‘kimono’ in the first place.

West explained the mark as serving the dual purpose of being a play on her name and showing respect for the Japanese culture. In fact, Kimono is Japanese for a traditional long, baggy garment that has been worn by Japanese women for centuries. Kardashian’s effort caused an uproar among the Japanese community in Japan and here in the United States. The community accused Kardashian of trying to exploit a centuries-old Japanese tradition for commercial gain.

Although the immediate controversy has now subsided, Kardashian’s truncated effort has renewed debate around the larger issue of “cultural appropriation” and its intersection with trademark law.

The controversy also prompted the mayor of Kyoto, Daisaku Kadokawa, to issue a statement urging Kardashian to drop the trademark of Kimono for her shapewear brand. In his letter, he wrote, “Kimono is a traditional ethnic dress fostered in our rich nature and history with our predecessors’ tireless endeavors and studies and the same should not be monopolized, He also went on to emphasize that the city is aiding Japan’s initiatives to get “Kimono Culture” registered to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list because the rich culture and heritage behind the garment shouldn’t be monopolized.

The Trademark Test

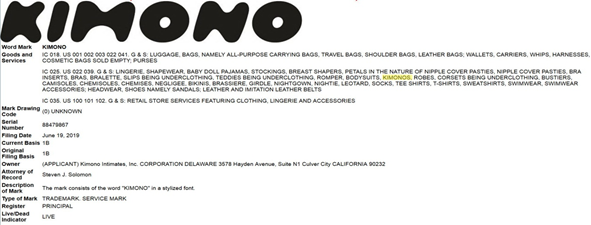

Although the original Trademark application has now been voluntarily amended omitting the terms, ‘Kimonos’ and ‘Robes’ under the Goods and Services category for the wordmark, a search on the USPTO website clearly shows the trademark application containing the two generic terms under the ‘KIMONO’ wordmark.

In fact, the word ‘kimono’ has been applied and registered 34 times in the USA. In Australia, Hasbro Inc, the large toy company, has registered the word ‘kimono’ for ‘toys and games and dolls in Japanese national dress’. Mayer Laboratories had registered the name ‘kimono’ for contraceptives in 2007. It would seem that Hasbro and Mayer have avoided the accusation of cultural appropriation. To be valid, a trademark needs to be distinctive enough to perform its dual identifying and distinguishing functions. Trademark law provides three categories of distinctiveness for trademarks: inherently distinctive, descriptive, and generic.

Inherently distinctive marks (fanciful, arbitrary, or suggestive) are inherently capable of acting as source identifiers. Descriptive marks, on the other hand, describe an aspect of the good or service they are used to identify. Descriptive marks are only valid if they have “acquired distinctiveness” or “secondary meaning,” meaning that consumers have come to associate the mark with the product or service it identifies. A generic mark refers to “what” the good or service is, and, as such, is not capable of acting as a source identifier for that good or service.

In India, such an application would be hit by Section 9(1)(b) of The Trade Marks Act, 1999 which provides for Absolute grounds for refusal of registration as the mark consists exclusively of indication and/or characteristic of the goods or services, particularly, the word mark. ‘Kimono’ for a traditional ‘Kimono’ dress.

Trademarks and Cultural Appropriation

The phrase ‘cultural appropriation’ is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “the unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society.” In the trademark world, culture and trademarks have always had a rocky relationship. Westernized and European-centric designers have historically been accused of stealing traditional designs, music, dances, and hairstyles for their own use and profit, while the minority groups from whom they took receive little more than an acknowledgment. Hence, corporations need to be more sensitive and aware than they have ever been when it comes to applying intellectual property (IP) to a print, shape, saying, or concept that is associated with a particular set of values, expression, and/or ethos of a group of people.

Appropriating ‘cultural’ symbols has been attempted in the past too. In the 90s, India had to fight a dogged battle against some American companies to protect the name ‘Basmati’ rice despite significant claims to GI-tagging. Those American companies in fact managed a trademark on ‘Kasmati’ rice and it took the Indian government a lot of legal expense and cross-country effort to protect its turf. The words ‘khadi’ and ‘yoga’ have seen pitched battles too. German company Khadi Naturprodukte almost managed an EU trademark not too far back on ‘khadi’ and it took a lot of legal wrangling to negate the foreign entity. It would surprise many to know that the US Patent and Trademark Office has reportedly issued 150 yoga-related copyrights, 134 trademarks on yoga accessories, and 2,315 yoga trademarks.

Conclusion

The lesson for brand owners, celebrities, and entertainers maybe that selecting a name derived from another culture involves more than just ascertaining whether it is available and registrable under a country’s Trademark Law. Consideration should be given to cultural sensitivities and the likely reaction in the marketplace to whether the name will be deemed offensive or inappropriate and ultimately bad for business.

Author: Himanshu Mohan, LL.B. final year student at Campus Law Centre, Faculty of Law, University of Delhi, Intern at Khurana & Khurana, Advocates and IP Attorneys. In case of any queries please contact/write back to us at niharika@khuranaandkhurana.com